Financial planner life expectancy tools putting retirees at risk

Retirement calculators should include a lifespan assessment that is fit for purpose!

Helping someone plan for retirement involves assessing different strategies and retirement products. Naturally, when considering the most suitable solution, it is important to estimate how long the person could live, and the best plan to fund this period.

Underestimate a retiree’s lifespan? They could outlive their savings. Overestimate it? That could mean an excessively frugal existence.

This issue has a huge impact on a person’s retirement lifestyle, happiness, and dependence on government funding.

There are many tools and calculators available to superannuation funds and financial planners for helping estimate life expectancy and help design the best-suited retirement plan. However, these tools are only as useful as the assumptions used, and recent research from the Actuaries Institute found that many of the tools available may not always reflect best practice when it comes to Australia’s increasing life expectancy and the wide range of lifespans different groups of retirees face.

The Actuaries Institute Retirement Incomes Working Group recently wrote a research note exploring this issue and made several recommendations for those building and using retirement calculators.

Using an average is not enough

Life expectancy measures the average for how long a group of people are expected to live based on age and sex-specific mortality rates. But if we only look at the average then we aren’t considering what will happen to all the other individuals in the group.

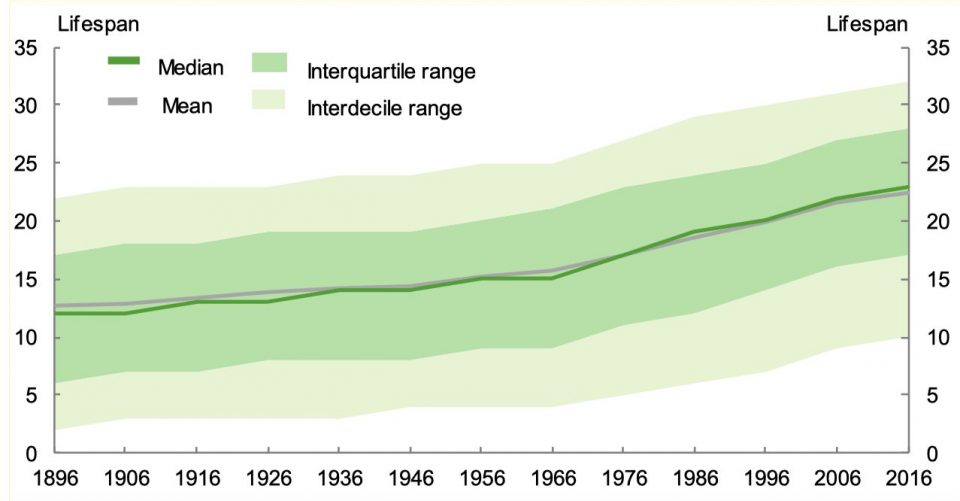

This chart shows the range of lifespans for 65-year-old females since 18961. It illustrates two of the reasons why simply using the average is not appropriate.

- There is a range of possible lifespans around the average as shown by the shading on either side of the median – approximately half (!) the population will live longer than average.

- The chart shows the increase in life expectancy over time. It’s important to remember that people who are currently in their 80s and 90s were born back in the 1920s and 1930s. Whereas today’s 65-year-olds were born in 1955.

From this, it becomes evident how it’s vital to allow for the range of possible lifespans that a person may experience as well as for improvements in life expectancy – not focus solely on the ‘average’.

Joint-life expectancy is longer than single life expectancy

When helping couples plan for retirement, using a joint-life expectancy is recommended. Joint life expectancy is measured from the age of the second death and exceeds either partner’s (single) life expectancy. Why? Because couples get two shots at beating the average and need to be prepared!

To illustrate the impact of this, if an adviser or superannuation fund has 1,000 healthy, educated, professional couples entering retirement, it could expect around half of these households to still have one spouse alive at age 95.

Quantifying longevity risk

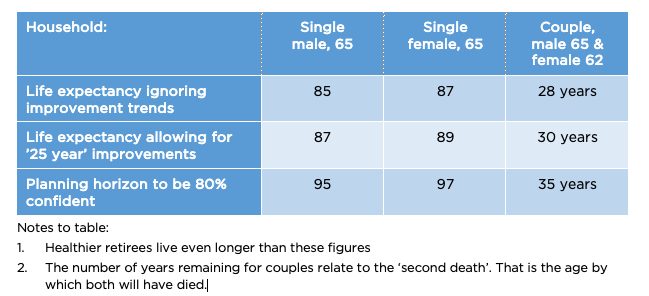

Simply stating that a 65-year-old female is expected to live to age 87 is careless and arguably as bad as ignoring investment risk!

The age of 87 is an estimate based on the Australian Life Tables 2015-172 (the most recent available tables from the Australian Government Actuary) but ignores the accompanying mortality improvement factors which are designed to allow for the fact that the chart above keeps increasing. The age of 87 is based on data from people who were born eight decades ago!

An average 65-year-old female born in 1955 needs to plan to age 89 for a 50/50 chance her retirement plan will last as long as she does. To be 80% confident that her financial plan will cover her whole lifespan she needs it to last to age 95. That’s around 10 years longer than the simple life expectancy. If she has a partner? Then they really need to plan to age 100 to be confident.

Applying these considerations to retirement planning, we also know that there is a different lifespan range that different groups of individuals experience depending on variables such as their current health status, nutrition, lifestyle, education levels, occupation and just plain luck. This could also result in retirees living too frugally or too excessively if projections are based on averages, as ignoring the specific circumstances of someone will lead to a misestimation of their risks.

Ideally, these factors should be considered as part of personal retirement planning and a team of actuaries are working on an online tool to personalise this assessment for every retiree. The assessment will take into account how confident retirees want to be about not outliving their savings (their ‘longevity risk profile’) – often overlooked. The aim is for more accurate lifespan projections and better suited retirement plans.

In the meantime? As a minimum, retirement professionals should check that the life expectancy calculation methods they use are fit for purpose to avoid retirees paying the price by selecting strategies and products that might not be in their best interests due to life expectancy shortcomings.

Find the Actuaries Institute research note here.

This article was originally published on the Optimum Pensions website. View the article here.

1 – ALT2015-17 Report by the AGA. See Figure 9, page 14 http://www.aga.gov.au/publications/life_table_2015-17/default.asp

2 – http://www.aga.gov.au/publications/life_table_2015-17/default.asp

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.