Net-Zero Targets

In this edition of the Climate Change Blog, Evelyn Yong and Alex Keywood explore what Australian insurers, reinsurers, and banks are doing to align to the goal of achieving net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by the second half of the 21st Century, and what it means to have an investment portfolio aligned to a net-zero target.

Actuaries have the opportunity to play a significant role in the economic response to the climate crisis, and understanding climate risk has become a higher priority for the profession. In September 2020, the Actuaries Institute released an updated statement on climate change. The first policy position in the statement is that the Institute supports the goal of the Paris Agreement to achieve net-zero emissions by the second half of the 21st Century.

In addition, the Institute recently released an Information Note for Appointed Actuaries on Climate Change. This paper provides guidelines for how Appointed Actuaries might incorporate climate risk measurement and management into their operations. It highlights that investment portfolios are exposed to transition risks, such as legislative changes and asset repricing due to climate events. Adopting net-zero investment targets can aim to reduce these risks by investing in climate-resilient assets.

In this edition, we explore how some Australian banks, insurers, and reinsurers are setting their net-zero goals to support development of effective responses to climate change, as well as discussing what it means for an investment portfolio to be ‘net-zero aligned’.

Measuring climate risk and emissions

Globally and locally, asset owners and lenders are developing standard metrics to monitor emissions by companies, classified by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol into Scopes 1, 2 and 3. Scopes 1 and 2 cover direct emissions and emissions from purchased energy, respectively. Scope 3 emissions include any that are downstream from a company. For a financial institution, this refers to emissions from underwritten assets and investment portfolios.

Financed emissions are the bulk of the output from the financial sector. Unfortunately, this emissions classification has the least development in measurement due to its complexity. In Australia, eligible corporations must report their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting scheme, but there is no requirement to report Scope 3 emissions.

Investors and underwriters rely on data to make their decisions, and financial companies have often cited a lack of consistent data as a barrier on understanding the emissions of their portfolios. In response, there is an ever-growing library of metrics and targets used to attribute emissions to businesses. The pre-eminent climate disclosure framework is the TCFD, released by an international group of asset owners for disclosing climate risk in 2017. Their 2020 Status Report shows that companies around the world are adopting the system.

Notable domestic examples of TCFD adoption include the Commonwealth Bank, who have been leaders in climate disclosure, and industry superannuation fund REST, who recently committed to climate risk disclosure after settling a lawsuit from a member. There are several other banks, insurers and superannuation funds that have committed to TCFD reporting.

The TCFD framework aims to allow investors to understand their own climate risk. Other groups, such as the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) have developed tools to allow businesses to develop their own net-zero targets. Below, we list several Australian examples of financial institutions’ targets.

Banking Sector

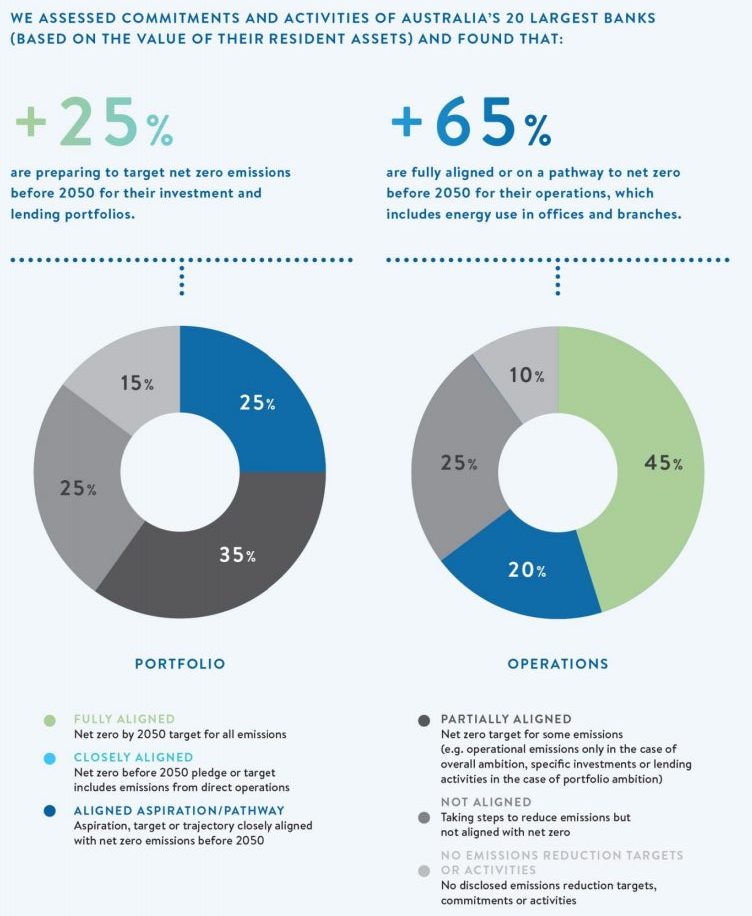

The Net Zero Momentum Tracker monitors Australia’s progress towards net zero emissions across key sectors of the economy. They published a report late 2019 that summarises the pledges and commitments in the banking sector.

Many of the banks analysed have set their emission reduction targets using the methodology from SBTi. Examples are:

- Suncorp targets 51% absolute reduction in Scope 1 and 2 GHG emission by 2030 (against 2017 baseline);

- NAB committed to reduce GHG emissions by 51% by 2025 (against 2015 restated baseline);

- Westpac committed to 34% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030; and

- ANZ recently committed to setting public targets to lower GHG by 24% by 2025 and 35% by 2030 (against a 2015 baseline).

The ‘big four’ banks have also committed to source 100% of their electricity from renewable sources through the RE100 initiative according to a case study by Net Zero Momentum Tracker.

Other commitments include limiting lending to coal mining or coal fired power generation, for example:

- NAB committed to capping thermal coal mining exposures at 2019 levels, reducing by 50% by 2028 and intended to be effectively zero by 2035. NAB will not take on new-to-bank thermal coal mining customers either.

- ANZ will not directly finance any new coal-fired power plants or thermal coal mines, including expansions. Existing direct lending will run off by 2030.

- Suncorp will not directly invest in, finance or underwrite new thermal coal mining projects or electricity generation, or new oil and gas exploration or production. Suncorp has a target to phase out existing thermal coal exposures by 2025, as well as phase out underwriting oil and gas by 2025.

Insurers and Reinsurers

Similarly, QBE targets 30% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 carbon emissions by 2025 (from 2018 levels). QBE stopped insuring new thermal coal mines, power plants, and transport networks from 1 July 2019, and committed to shut down its thermal coal underwriting business by 2030.

Some reinsurers commit to net zero by 2050 and express their commitments in terms of operational emissions:

- Swiss Re has committed to reducing air travel emissions by 30% in 2021 via their CO2NetZero Programme. Swiss Re also commits to carbon removal projects to compensate emissions, for example, afforestation, direct air capture or mineralisation.

- Munich Re compensates carbon emissions in their business operations by purchasing carbon certificates with strict requirements when selecting offsetting projects. The project must meet standards and be implemented in less developed countries.

Net-zero portfolios

Measuring emissions and executing an emission reduction plan are complex projects. Several of the accounting standards and risk analysis frameworks outlined above are still in development and are adopted on a voluntary basis. (New Zealand recently became the first country to introduce mandatory TCFD reporting, which begins in 2023.)

While these frameworks exist to make comparing the emissions of companies easier for investors, this work does not need to be finalised for asset owners to move to a net-zero aligned portfolio, if not a portfolio that is already carbon neutral.

A portfolio of bonds issued by governments with net-zero emissions targets (such as any state or territory in Australia) would be considered in-line with a net-zero emissions target, according to the UN Principles for Responsible Investing. This might change should the issuer fall behind on its targets. There are several methods for attributing emissions to debt securities, but global standards are still in development.

Green bonds are a rapidly growing portion of the corporate and government debt markets, but the term is currently prone to greenwashing. In response to this, the EU has developed a Green Bond Standard, a set of recommendations which is currently under consideration for a legislative initiative by the EU. The Standard works in tandem with the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, a broad set of classifications designed to assist investors in assessing sustainability.

Equity investors who focus on emission reduction generally have three methods available to them:

- Divestment or exclusion from high-carbon industries, such as mining or airlines.

- Stewardship of companies as active shareholders, to encourage them to enact strong emissions plans.

- Offsetting emissions through the purchase of carbon notes such as Australian Carbon Credit Units.

While equity holdings at insurers and reinsurers are generally low, consistently depressed interest rates have encouraged these companies to invest more of their significant reserves into riskier assets, including equities and illiquid alternatives.

Conclusion

There are many ways that Australian financial institutions can reduce their emissions, both operationally and in their products. As climate change worsens actuaries will need to keep transition risks in their portfolios in the forefront of their minds. Understanding these risks is a considerable task, but global and local leaders continue to work to develop standards and frameworks, and set examples for others to follow for net-zero emission plans, including financed emissions.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.