Climate risk disclosures: The scientists are talking. Are we listening and how should we respond?

Recently, a number of scientists have drawn attention to the challenges faced by businesses in undertaking climate risk assessments. This article sets out a potential five-phase approach to help increase our understanding of the physical impacts of climate change, which could form the basis of disclosures in the interim.

Central to the scientists’ viewpoint is the difficulty in predicting how the frequency and severity of the more extreme weather events will change at local situations where individual business assets are held.

|

“I think there is at least a decade between what you (APRA) are suggesting businesses do, and what climate science can usefully inform them about.” 2020 Paper by Fiedler et al 2021, titled Business Risk and the emergence of climate analytics. |

In undertaking climate risk disclosures and assessments of physical risk, we need to be mindful of creating a false sense of accuracy by using complex tools with uncertain underlying science. There is a risk that in some cases, complete physical risk assessments in the short term will lead to spurious and arguably meaningless disclosures. The analysis remains a necessary and important task, but we need to avoid getting ahead of ourselves by understanding this uncertainty and factoring it into our approach and our advice. So, what might that look like? The remainder of this article sets out one possible approach.

In the Fiedler et al (2020) paper, the authors propose scientists working with business to develop climate projections that are fit for purpose. This is important work and needs investment from business. But it is not a quick fix and according to the authors might take at least 10 years.

Even before fit for purpose climate projections are available, there is additional work that can be done and needs to be done to increase our understanding of the physical impacts of climate change, and that could form the basis of disclosures in the interim.

Central to the approach is that the path to full quantification of the risk does not need to be rushed. There is plenty to be learned at each stage.

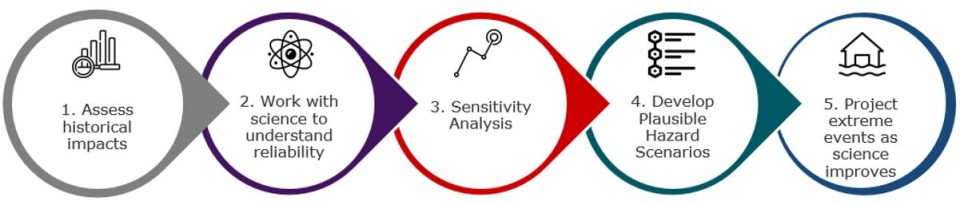

The following phases of work are proposed:

We discuss each of these below:

- Assess how your business has been affected by historical extreme weather events. For example, by past catastrophic events and past variations in El Niño–Southern Oscillation. If there is evidence that past weather has impacted your business, then you need to be taking the assessment of physical risk very seriously. For general insurance companies, this link is clear. Some other industries will not be affected to the same extent. Ultimately, businesses also need to consider if any new types of events (unprecedented in severity or in this location) can impact their assets in the warming world. A key outcome from this phase would be an understanding of all the types of weather extremes that can impact the business.

- For the types of weather extremes the business in susceptible to, work with the scientists to understand which ones can be predicted with some reliability and which ones can’t. For example, temperature extremes or sea level rise may fit in the first category, whereas cyclone behaviour may fit in the second.

The following steps are proposed for those hazards where prediction is problematic:

- Undertake a sensitivity analysis. For example, how cyclone costs by region will change given a poleward shift in cyclones of 100km, 200km and 400km. Or how the costs of riverine flood will change in different areas for a 5% and 10% increase in rainfall intensity. Such a sensitivity analysis will tell us a lot about the risk even before we know what level of increase is most likely. We will be able to understand key risk drivers, key regions of risk and tipping points (i.e. what level of change in the hazard leads to an abrupt increase in the cost or irreversible change?).

- The fourth phase of work is the development of plausible hazard scenarios (as distinct from warming scenarios) and using such scenarios to estimate how costs could change. This would involve engagement with meteorologists and climatologists to agree on plausible changes for each type of extreme events or phenomena. So, by way of illustration (figures are indicative) a modest scenario for cyclone hazard change might look something like:

-

- Frequency reduces by 10% (such assumptions might vary by region).

- Wind speed increases by 5%.

- Rainfall increases by 10%.

- Slower moving over land (longer duration of sustained extreme winds and rainfall).

- 100km poleward shift.

- Sea levels 50cm higher.

- Frequency reduces by 10% (such assumptions might vary by region).

There would be no assignment of such a scenario to a timeframe or specific warming scenario, recognising this is not possible to do at this stage (if we listen to the scientists). We could however describe the scenarios in broader terms, for example ‘modest’ and ‘severe’ plausible scenarios. Some companies may want to loosely attach the scenario to a warming scenario for compliance purposes. The Climate Measurement Standards Initiative (CMSI) has undertaken some excellent work in this area to provide a starting point for the development of relevant scenarios, although there is more work to be done in considering the tail risk which is most important to many companies.

- Later as the additional research is undertaken and under each of the warming scenarios the projection of future extreme events becomes more reliable on the required temporal and spatial resolution level, the industry will be well placed to combine the hazard scenario analysis with the extreme event projections that emerge from the collaboration of the scientists and the business. Only at this step, businesses should be expected to be able to provide reliable physical risks assessment costs against the warming scenarios. Industry needs to invest in this research to make it a reality.

The proposed approach can be used to deliver meaningful disclosures in relation to the risk that keep pace with the ability of the science to forecast extreme events.

A key question is whether the users of disclosures will be satisfied with sensitivity and hazard-based scenarios analysis in the short to medium term for certain hazards, with the warming scenarios probably being more than five or ten years away.

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.