Climate Finance: Tracking the Funding of our Future

Climate finance refers to financing that supports mitigation and adaptation actions to address climate change[1].

The Paris Agreement calls for financial assistance from parties with more financial resources than those that are less endowed and more vulnerable, recognising that countries vary enormously in their capacity to mitigate climate change and their ability to cope with its consequences.

This article aims to highlight the key points of the Climate Policy Initiative’s Paper on the Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023[2] (the Landscape). The Paper was made available to inform the Conference of the Parties #28 (COP28) held 13 November 2023 to 13 December 2023, in Dubai.

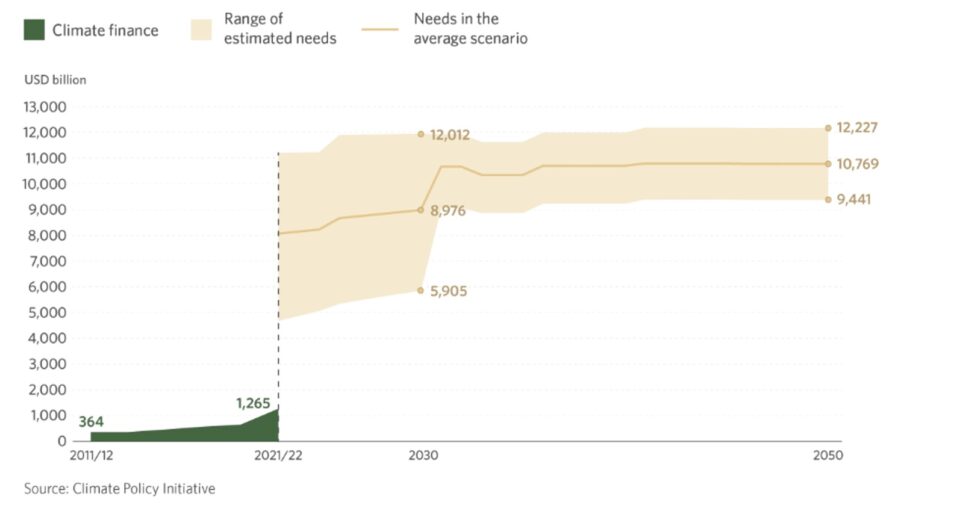

Global climate finance increased by 16%, or USD 1.265 trillion, from 2019/2020 to 2021/2022. This was partly through improved data and methodology, and is still way below what is needed, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Global tracked climate finance and average estimated annual needs through 2050[3]

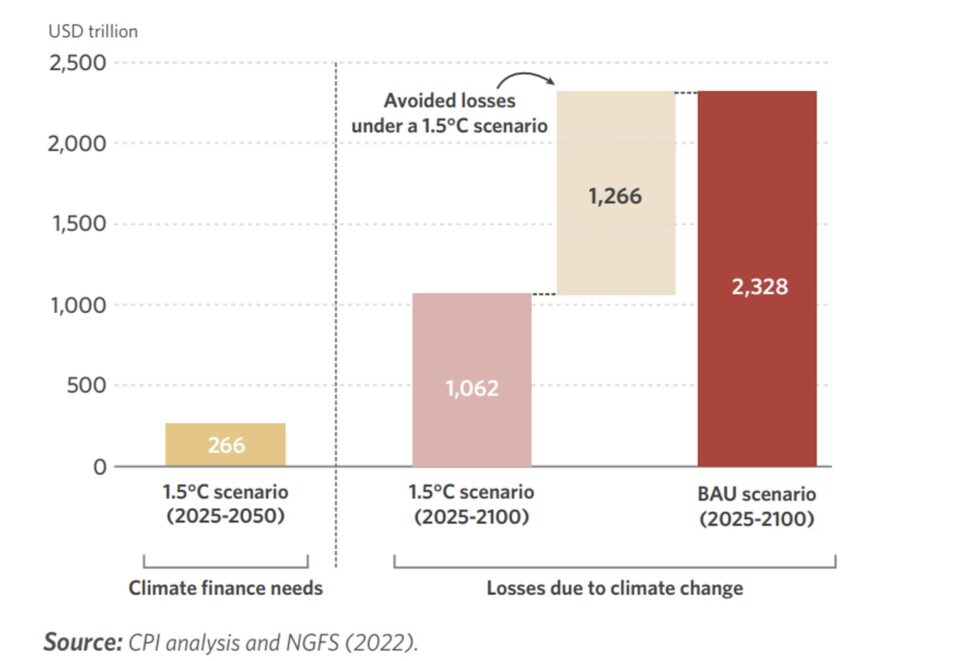

If climate finance needs are not met, the costs of mitigating global temperature rise and addressing its impacts escalate rapidly. Figure 2 compares the climate finance needs and projected climate change losses under the Paris Agreement temperature target of 1.5oC[4] compared to a Business as Usual (BAU) scenario.

Note that the BAU losses are likely dramatically understated, as losses such as stranded assets, nature and biodiversity losses, and other human impacts are not included.

Figure 2: Cumulative climate finance needs vs. losses under 1.5oC and BAU scenarios[5]

CPI: Climate Policy Initiative; NGFS: Network for Greening the Financial System

The following sections discuss the growth of climate finance by sector and geography.

Global climate finance by sector

Energy and transport

These are the two largest emitting sectors, with private finance dominant. Energy attracted about 44% of mitigation finance, and transport about 29%. There has been a steep rise in the sale of electric vehicles (EVs) led by China, Western Europe, and the US.

Agriculture and industry

These sectors are the next largest sources of emissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) project their combined mitigation potential to be larger than that for energy and transport by 2030.

At present, they receive a disproportionately small amount of global finance (less than 4% of mitigation and dual benefits finance).

Emerging technologies

Technologies such as battery storage and hydrogen usage are starting to attract private finance but are far from achieving their potential scale.

Finance to meet adaptation needs, like that for mitigation, falls well short of what is required. It is almost entirely publicly funded.

Geographical concentration

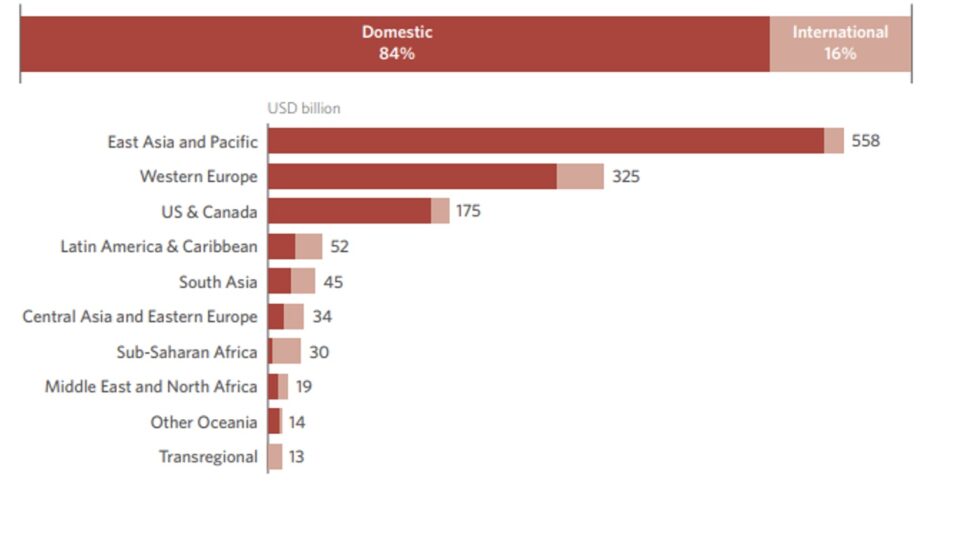

Developed countries generate the most climate finance, primarily from private sources.

East Asia and the Pacific, US and Canada, and Western Europe raise 84% of total climate finance, and are ahead in mobilising domestic sources.

China’s domestic generation of climate finance was larger than all other countries combined, with 51% of global domestic finance.

Globally, climate finance increased by 35% from 2019/20 to 2021/22, primarily through increased commitments from developed economies (84% of international climate finance).

Emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) including China, commit 13%. Less than 2% was committed for countries in the global south, mostly from public sources, and mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean followed by East Asia and Pacific regions.

Despite the increase, climate finance flows continues to fall short of needs, particularly in developing and low-income economies. Around 18% went to less developed countries (LDCs) and EMDEs (excluding China). The 10 countries most impacted by climate change between 2000 and 2019 received only USD 23 billion, less than 2% of total climate finance.

Figure 3: Domestic and international climate finance by destination region[6]

Private fiance

Private finance is growing and provided 49% of total climate finance in 2021/2022 at USD $625 billion. Developed economies are much more successful at raising private finance than EMDEs, but the rate of increase is still too slow.

The largest private sector growth came from household spending and reached 31% of all private finance. This is the highest since CPI started recording this more than 10 years ago. The main driver was the purchase of electric vehicles which doubled from 2020 to 2021. Fiscal policies generally supported this activity.

Development finance institutions provide the majority of public finance, accounting for 57% of public climate finance. But more than 17% of public finance for LDCs is in the form of market-rate debt, which just increased the indebtedness of these countries. Thought needs to be given to the strategic use of public funds and other concessional capital to not unnecessarily increase the burden on LDCs and to mobilise private capital to assist.

Scaling the quantity and quality of climate finance

There are many ongoing crises calling for attention, but the pressure to turn climate commitments into deployed climate finance, both public and private, is increasing.

CPI has made several recommendations to accelerate climate finance deployment.

These include:

Transforming the financial system: Build on momentum to reduce the cost of capital and expand 2050 targets by establishing transparent and shorter-term plans focusing on the real economy.

Bridging climate and development goals: Align development and climate agendas to accelerate action on both fronts, while increasing understanding of climate risks. Plan to phase out fossil fuels through a just transition.

Mobilising domestic capital: Align Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) with the Paris Agreement 1.5oC goal to generate consistent domestic policy and investment signals. Build capacity and stronger enabling environments to bolster domestic private capital, particularly for EMDEs.

Acting to improve data: Simplify and standardise taxonomies across countries. Make data more consistent, standardised and available across jurisdictions, to boost understanding of climate change and finance.

Looking forward

Pursuing low-carbon and climate resilient development makes the most long-term economic sense, and winning the public debate across all groups on the urgency of action is vital. Climate investment is necessary to achieve the Paris Agreement goals and to achieve longer term development, resilience and security.

References

[1] United Nations Climate Change. (2024). Introduction to Climate Finance. https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance

[2] Buchner, B., Naran, B., Padmanabhi, R., Stout, S., Strinati, C., Wignarajah, D., Miao, G., Connolly, J., & Marini, N. (2 November 2023). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2023; Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2023/

[3] United Nations Climate Change. (2024). Introduction to Climate Finance. https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance

[4] The Paris Agreement has a long-term goal of holding the global average temperature increase to “well below 2°C above preindustrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”.

[5] United Nations Climate Change. (2024). Introduction to Climate Finance https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance

[6] United Nations Climate Change (2024) Introduction to Climate Finance https://unfccc.int/topics/introduction-to-climate-finance

CPD: Actuaries Institute Members can claim two CPD points for every hour of reading articles on Actuaries Digital.